Contents

Everything you need to know about Safety Management and Organization

[wpecpp name=”package” price=”75″ align=”center”]

by L. Harvey Kirk III, CSP*

Innovations in cement safety and health have enabled the industry to move beyond what was once considered the ultimate in progressive methodology, that is, 20th century ideas and thought. Revolutions in technology and control have improved John Smeaton’s basic commodity and Joseph Aspdin’s simple process immensely. Market expansion, global ownership, and interna-tional financial considerations have changed the face of cement manufacture forever. As witnesses to such great evolution, and surrounded by such marvelous testaments to man’s ingenuity, creativity, and paradigm-breaking imagination as modern cement manufacturing plants, the indus-try should also strive for similarly remarkable advances in leading edge safety performance.

INDUSTRIAL COMMONALITIES

Just as the disciplines of business management and engineering have basic precepts and principles that govern their application and are recognizable in any well-run company, numerous commonal-ities exist in occupational health and safety, regardless of industry. The results of fires, falls, and mobile equipment collisions; contact with electricity, machinery, or power transmission devices; and back and eye injuries are just as incapacitating and devastating whether they occur in a cement plant, sand and gravel operation, coal mine, chemical plant, or on a construction site. Cement is a unique product, a part of the larger construction materials industry, and its manufacturing process is considered by some to be a unique hybrid of the mining and chemical industries. Because the cement industry utilizes similar equipment and wrestles with similar hazards, the safety successes of these related industries can be instructive. For success in the 21st century, the cement industry should not be introspective, but should benchmark the best ideas of related industries, and apply those that have demonstrated benefit.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Although great strides have been made in injury prevention, still to be overcome are issues with which the mining industry has struggled for hundreds of years. However young the cement indus-try may be in the course of human events, one can always look back at mining and milling history to see safety framed as an important industrial issue. In his classic and exhaustive 16th century treatise on mining, De Re Metallica, Georgius Agricola (1556) listed a handful of competencies required for a mine operator to be successful. Listed on a par with geologic discernment, mathe-matics, various engineering disciplines, and law was “Medicine, that he (the mine owner-operator) may be able to look after his diggers and other workmen, that they do not meet with those diseases to which they are more liable than workmen in other occupations, or if they do meet with them, that he himself might be able to heal them or may see that the doctors do so.”

Agricola (1556) further put the industry in perspective when he stated, “It remains for me to speak of the ailments and accidents of miners, and by the methods by which they can guard against these, for we should always devote more care to maintaining our health, that we may freely perform our bodily functions, than to making profits.” In an early chapter, he voiced a priority for health, safety, and injury prevention. He addressed rockslides, cave-ins, fall and water hazards, harmful dust, vapors, fumes and mists, heat exhaustion, and cold weather hazards. He established important precedents for modern health and safety concepts like engineered ladder and scaffold safety, establishment of positive ventilation and air exchange, eye and respiratory protection, and management and supervisory responsibility for safety. The woodcuts that illustrate his book detail for the less sophisticated reader complex mining processes, equipment design and construction, and show elaborate ventilating systems, respirators, various means of fall prevention, and applied ergonomics.

DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY

In these safety and health chapters, certain terms and words have been chosen and used in a manner consistent with the emphasis on prevention in safety literature and safety programs. Incident signifies an event, and has been used instead of accident, because accident may convey a sense that an event is unpreventable or unpredictable.

At-risk behavior has been used instead of the older term unsafe act.Behaviors are observable events, and are inherently neither good nor bad, just risky or safe. Only when used in conjunction with such modifiers as “willful” or “conscious” do they describe a person’s attitude or motive. Unsafe act is too often construed judgmentally or as a presupposition of an individual’s motive. If, during communication, the term is perceived to have other than constructive intent, it can become a bar-rier to preventing subsequent recurring behaviors that place persons or equipment at-risk and lead to serious incident outcomes. At-risk behaviors may be an immediate cause of an unsafe condition.

Safety process has been used to indicate the overall, continuing effort to blend safety into every aspect of the operation. Production, quality, and cost management efforts are regarded as everyday activities, and safety should be likewise. Programs connote a subsection of the whole, or something with a beginning and an end, so using the term safety program too loosely could lead employees to believe safety is something which is intermittent, or which is emphasized more at certain times. Where program is used, it is to designate a specific element of the safety process, such as “hearing conservation program.” Processes, like kiln or mill operations, are considered 24 hour per day, 7 day per week efforts, so using the term together with “safety” as much as possible signals that safety, too, is a never-ending effort.

Risk is the probability of harm, and hazard is the source of risk (Markiewicz, 2000). Safety is the freedom from risk or occurrence of injury, illness, or incident. The practice of safety uses tools to anticipate, recognize, evaluate and control hazard and risk, and reduce, eliminate, or prevent injury, illness, or incident. Therefore safety is: 1) a state, 2) a discipline and a science, and also 3) a lofty premise, in itself a goal that demands just as much attention to continual improvement as do quality, production, cost control, profitability, or customer service.

HEALTH AND SAFETY: A TEAM EFFORT

The safety team is comprised of executive and line managers; hourly leaders; production, mainte-nance, and support staff personnel; medical providers; and occupational safety and health profes-sionals, all linked together in a common cause. Active participation and involvement of all are vital to an effective safety and health process (Plog, et al, 1996.) Weaknesses or breaks in the chain jeop-ardize the entire effort and put at-risk the industry’s most valuable resource, the individual cement plant employee. Occupational safety and health staff members are found within the organization in a variety of positions and, depending on a company’s organizational structure, fulfill different roles and have differing amounts of responsibility and managerial authority.

Corporate Safety and Health Personnel

Safety and health persons in corporate or divisional positions provide technical guidance and expertise to top management. They collect and analyze data from all quarters of the company and produce reports to identify trends, strengths, and improvement opportunities. They are the resource to which plant management and facility safety personnel often turn when there is a need to gather and distribute useful information and best safety management practices, or help coordi-nate or standardize programs, policies, procedures, equipment, and reports. Corporate safety and health personnel are found in safety, human resources, legal, community relations, manufacturing, and technical/engineering departments. Corporate safety personnel should have experience or training in safety management and organization, and be highly knowledgeable about technical safety, health, and industrial hygiene issues. Many have formal post-secondary safety and health training, possess expert knowledge obtained through many years of experience, and hold advanced degrees or certifications in safety and health.

Facility Safety Personnel

Safety at manufacturing facilities is usually coordinated by someone at that site dedicated to safety and health issues. When this is not feasible due to the size of the company or the facility, certain safety coordination and reporting functions can be performed by corporate level staff, assigned to someone as one of several responsibilities, or divided between several persons. An important concept to be understood by all is that safety should not be viewed as the responsibility or job of the safety and health staff alone. Safety is a line management responsibility; therefore managers and supervisors should be expected to address safety, as well as production, costs, and quality. Likewise, safety and health persons alone should not be expected to enforce or police safety, or performance may be spotty, inconsistent, or poor.

Duties of the plant safety professional include: 1) serving as a technically expert resource on issues pertaining to safety and health for the plant manager, line supervisors, engineers, purchasing personnel, hourly workers, and the joint safety and health committee, 2) coordinating, monitor-ing, keeping records, and producing reports regarding the plant safety process, 3) coordinating, providing, and recording safety-related training, 4) serving as a plant liaison with regulatory offi-cials, safety representatives at other locations, and various groups within the safety community, 5) coordinating or performing audiometric testing, noise, dust, and other health and industrial hygiene surveys, 6) coordinating the workers compensation process, and 7) maintaining a library of safety resource materials and material safety data sheets.

Specialized knowledge for someone in this position should include a working knowledge of:

1) basic and applied sciences, 2) safety management, organization, legal, regulatory, and ethical Safety Management and Organization

principles, 3) fire prevention, protection, and life safety codes, 4) principles of safe equipment and facility design, hazard recognition, and controls, 5) health and industrial hygiene principles, hazard recognition and controls, 6) best safety work practices specific to the cement industry, and 7) best safety practices for general industry hazards. Specific training related to occupational safety and health issues is particularly advantageous, as are computer skills and experience in an industrial manufacturing environment. Good interpersonal, oral, and written communication abilities are needed to communicate effectively with management and employees.

Professionalism

In the past, many safety persons had little or no safety background when they entered their job. A majority transferred into safety from operations, human resources or engineering departments, but recent trends are to recruit and hire trained or degreed safety specialists to coordinate safety efforts. A number of colleges and universities have specialized associate, bachelors and masters degree programs in safety science, industrial hygiene, and safety management, and professional safety organizations provide courses leading to certificates of competence or board certification. Safety staff can take advantage of these opportunities to obtain a solid safety foundation or to continuously upgrade their knowledge and skills.

Safety and health personnel should be encouraged to continue their safety education and improve their professional skills. They should enroll in specialized courses, attend safety conferences, participate in professional societies, subscribe to safety and health periodicals, and study for professional certifications.

MANAGEMENT ASPECTS AND ORGANIZATIONAL PRINCIPLES

A total quality, process-based approach to business includes a continuous demonstration of safety leadership, commitment, and involvement. These qualities are cornerstone principles of companies that achieve world-class safety performance.

Certain key business principles exist in most recognized world-class organizations. Although they are sometimes more readily associated with management, financial, and production concepts rather than safety, they are applicable in all settings. They are crucial to any successfully managed process, and their application to safety and health should be a logical extension from one business arena to another. These key principles are: 1) strategic and long range planning, 2) leadership, 3) effective management systems, 4) responsibility and accountability, 5) ownership, empowerment, and motivation, 6) open communications, 7) information and measurement systems, 8) training and education, and 9) implementation of effective practices and procedures.

STRATEGIC PLANNING

Management consultant George L. Morrisey (1996) suggests that management must first assess what an organization’s strategic values are or should be, and then develop its perspective for the future. He recommends identifying and concentrating on 8 to 10 values that will have a major impact on the future, and suggests ethics, quality, environment, industry and community image, responsiveness to customers, market and product diversity, strategic alliances, and expansion. He then advises, “If you are in an industry like chemical manufacturing, mining or transportation, safety had better be at or near the top of your list of values.”

Morrisey (1996) believes the most important use of the list of strategic values is as a ready refer-ence for developing the organization’s mission, vision, and strategy. He asserts the vision statement should be almost entirely values-based, its purpose being to provide an inspirational and motiva-tional picture of where the organization is headed. Whereas a published list of corporate values may be extraneous for public consumption, it is highly desirable for important stakeholders like customers, employees, and owners.

Consistent with his advice, safety should be ranked high on the list of corporate values, its importance communicated widely and thoroughly, and used to help determine strategic factors. Although safety will not be considered the objective that determines the scope and direction of the corporation’s future (Tregoe, 1980), it should be considered a major influence in long-range planning, and a critical issue worthy of inclusion in long-term objectives. It follows that safety should therefore be in an organiza-tion’s strategic action plan as an area for key results, with performance indicators identified.

Value vs. Priority

Joseph A. Holmes, first director of the Bureau of Mines (U.S. Department of the Interior, 1976), coined the phrase “Safety First” early in the 20th century, and safety awards are given in his honor to this day by the association that bears his name. With all respect to Mr. Holmes and the “Safety First” tradition, modern safety theorists no longer think safety should be the first priority. In fact, most now believe safety should not be regarded as a priority at all. Priorities change with conditions, such as when production lines are operating at reduced capabilities or are down for maintenance. At times like these, if safety is a priority, it may lose its Number One status. Relegation to second place may happen unconsciously or unintentionally by well-meaning employees or supervisors. Even temporar-ily displacing safety from its stated top ranking may lead some to question its value or lose their commitment to safe work procedures. This could carry over as a long-term problem.

Many world-class companies have improved safety and enhanced total operational performance by consciously removing safety from the list of corporate priorities. They have adopted safety as a core value and associated it with each activity, weaving it into the very fabric of production, cost and quality: every facet of the operation. Since values are closely held, unalterable beliefs by which persons or corporations conduct their affairs, these ideals and principles strongly and positively influence the culture of an organization.

LEADERSHIP

Experienced, competent, committed, involved, and forward-thinking leaders are crucial in a successful business. These leaders know that with their authority comes a responsibility that stretches the length and breadth of their sphere of influence. Those who apply total quality (TQ) principles also know that growth and continuous improvement in every process are bedrock issues for business and recognizable elements in any organization striving for world-class status. Safety is one element by which world-class status can be measured, a metric that, if lagging other indicators, will hamper progress toward all goals.

Cement manufacturing, like most industries, is a shared risk environment. On one hand, workers and their families bear the physical, emotional, and financial burdens that accompany negative outcomes when the safety system breaks down. On the other hand, ownership and management lose valuable employee services, and experience financial losses from medical and other worker’s compensation costs, equipment damage, and process interruptions.

Because of this duality of risk, leadership is comprised of more than the management team. From the chief executive officer (CEO) to first line supervisors, managers and supervisors are important members of leadership, but leadership also includes many others who influence the culture: union officers, shop stewards, crew lead men, safety committee members, and respected members of the hourly group. Hourly leaders have a tremendous influence on the safety culture. Where workforces are unionized, union leadership has an obligation to its members to promote a safe workplace throughout the year. By their speech, body language, actions, and work priorities, every sector of leadership—official or unofficial, traditional or non-traditional—sends clear and unmistakable messages about safety’s prominence and importance in the organization.

Safety will be reinforced as a value in the workplace to the degree in which leaders verbally support the value of safe vs. at-risk behavior, participate on safety committees, and model safety instead of risk-taking in their daily work practices. No one in any leadership position should ever use safety as a tool to gain or exert power, because this depreciates safety and contributes to injuries. Keeping safety “above the fray” will reinforce what should be its sacred position.

BENCHMARKING MANAGERIAL EXCELLENCE

At the direction of its CEO in the mid-1990s, an international minerals commodities and construction materials firm embarked upon a year-plus benchmarking project to study best-in-class safety processes. It examined international companies with top safety records and reached important conclusions about the role executive management plays in safety in world-class compa-nies. Conclusions were that if top management is to expect safety excellence, it must actively support it by: 1) communicating to all levels that quality safety performance is a requirement, not an option, 2) setting standards and goals, 3) making decisions and providing resources that support safety and 4) taking personal action that demonstrates commitment to safety. This firm also learned best-in-class companies have written safety policies signed by their CEOs, and that the higher in an organization safety representatives were placed, the greater the importance manage-ment is seen to attribute to safety. After implementing its new safety system at sites around the world, lost time injuries were reduced by about two-thirds (BHP Minerals, 1995).

Numerous CEO’s in construction and chemical manufacturing industries have adopted a “zero injury” policy, wherein they have decided to change the company culture from “some injuries are expected” to “no injury is acceptable.” They believe that setting injury goals higher than zero will prevent their company from reaching its business and profit potential. Expecting to incur more than zero injuries sends a message that up to a certain level, injuries are acceptable and there is latitude to sacrifice safety in the interest of production, schedule, or cost (Nelson, 1998). This can undermine the very condition management should be seeking – the cultural platform where personnel focus their attention on eliminating unsafe conditions and at-risk behavior, and prevent work-related injury, related costs, and interruptions (BHP Minerals, 1995).

Other ways management can demonstrate commitment are by including safety in business plans, placing safety on the agenda of management meetings at all levels and making safety a topic of discussion with subordinates. If safety is espoused, but becomes invisible in management plans, decisions and conversations that revolve totally about production, costs, and product quality, organizational subordinates might consider safety’s value to be low, and adopt this policy as their own. However, if safety is seen to be important to one’s superior, it will become important to subordi-nates as well, and to their reports. When managers are consistent, provide resources, reward and recognize safety achievements, and model safety personally, they can expect continuing safety improvement and an increasing percentage of proactive, rather than reactive, measures. A good example of top management taking a leadership role in safety is found in the Australian minerals industry. When CEOs attend Minerals Council meetings, safety and health is their first agenda item. The executives discuss fatalities and significant incidents, and individually present their personal efforts to improve safety performance in their own organizations. CEOs also lead an annual seminar focused on communicating safety and the role of leadership (Minerals Council of Australia, 2002). A growing number of firms and some industry associations in the construction and mining industries are adopting these concepts. They have seen lost time and recordable injury rates – and related costs – plunge to fractions of the industry average.

DRIVING FORCES AND MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

Although it is unlikely that safety will be the driving force in any company, there will be a driving force for safety. That force will shape the company’s safety philosophy and management principles, determine safety’s prominence in the organization, and influence safety outcomes, statistics, and trends.

There are four principal factors that can drive safety: 1) humanitarian concern, 2) cost contain-ment, 3) regulatory compliance and 4) business competence. Each has a role in today’s industrial reality. Which factor executive management chooses as the principal driver, and the rank and rela-tive importance of the others, determines which of the following four general safety management systems will be employed: 1) traditional program, policy and procedures systems, 2) inspection and auditing systems, 3) behavior-based safety, or 4) management planning and control systems. Companies may choose one of these systems, let one evolve in the absence of management direc-tion, or shape their own by incorporating the best features of each.

Policy and Procedure Systems

According to Donald Eckenfelder (1996), safety policy and procedure systems originated amidst mid-20th century efforts to bring a more humanitarian face to industry and to minimize insurance costs. These systems focus on programs, training, education, persuasion, worker attitudes, actions, skills, and close supervision. Measurement is usually downstream, primarily a count of negative safety outcomes. These systems are often discipline-driven, creativity is sometimes stifled, the culture is rarely influenced, and safety outcomes tend to be random and fluctuate.

Inspection and Auditing Systems

Eckenfelder (1996) describes inspection and auditing systems as evolutions or mirrors of the regu-latory process. They mainly address condition-related issues, not the cultural or at-risk activities that account for a high percentage of safety-related incidents. They rely heavily on detailed in-spections and physical site audits. Creativity sometimes suffers in this environment too, and fear can be an overriding factor; that is, failures beget sanctions. As in policy and procedure systems, measurement is downstream and it is safety failures that are counted. Nevertheless, one cannot dispute that regulations and repeated inspections have had a tremendous impact on the loss prevention process.

Behavior-Based Safety Systems

Behavior-based safety (BBS) has been on the rise since the 1980s. BBS is rooted in psychology and influences the culture by driving safety deeper into the organization. It makes employees more responsible for safety performance, but it tends to allow (or sometimes cause) management to step aside. When management and workers truly commit to this process, BBS can be effective in reduc-ing incidents, but results of such a process are often slow to realize and hard to quantify. In addition, manpower requirements can be large, follow-up can be intensive and in many cases BBS does not provide a measurable return on investment (Eckenfelder, 1996).

Statistics show that about 90% of incidents result from at-risk behavior. In a BBS approach, both risks and safe work practices are observed, measured and reported to gauge the effectiveness of the safety process. BBS systems have traditionally studied historical data to identify numerous critical behaviors that contribute to incidents and injuries. Trained observers then identify employees placing themselves at risk, correct them and help devise alternative safe work practices. Newer applications of BBS key on a Pareto-analyzed set of core critical behaviors and certain states, such as rushing, frustration or complacency, which usually precede errors. Focusing on smaller sets of behaviors and human factors permits employees to self-identify pending at-risk activity before it occurs and police their own work habits. It helps co-workers recognize risky situations before an incident occurs, makes intra-crew positive intervention easier and reduces the need for observers to leave workplaces elsewhere in the plant (Wilson, 2002). Once touted as the key component of a modern safety system, BBS is now acknowledged as but one more important part of an integrated and complete safety process.

Management Competency Systems

A fourth system is found in many companies whose safety processes are recognized as world-class, and in some consciously aspiring to achieve such a level. These companies have adopted safety as a corporate value and made safety a core management competency. Once an expectation of safety competence is adopted as a corporate business philosophy, top management commits to safety excellence just as any other business function, and clearly articulates and communicates its support throughout the organization. Objectives, strategies, and goals are established for all levels, respon-sibility is acknowledged from the CEO down to the first line supervisor, and vocal leadership and deep involvement reinforce values. Unsafe conditions, at-risk behaviors, and incidents are seen as symptoms that something is amiss in the management system (American Society of Safety Engineers, 1991), and actions are taken at the root cause level to prevent recurrence and improve the system. Incident prediction and prevention are sought, and proactivity is stressed over reactiv-ity. Metrics include upstream aspects of the safety process, not just outcomes.

Phelps-Dodge Corporation (PDC) is an international mining firm long recognized as a leader in safety. It once judged safety performance on numerous technical components that comprised its safety system, but the company now measures safety along a continuum of competency in key management and organizational principles. PDC judges an operation’s safety performance on how health and safety are affected by site management’s competence in managing accountability, communication, change, and other business issues (Hethmon, 2000).

RESPONSIBILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Safety is a personal responsibility and everyone’s job. However, the legal responsibility for safety embodied in certain safety statutes, regulations, and worker’s compensation laws falls squarely upon management.

Management of the safety process should follow the same blueprint as any other company func-tion. Therefore, a framework for safety with levels of responsibility and accountability should be established within every company and facility. World-class chemical and mineral products compa-nies that make safety a core competency for line managers and executives provide managers at each level with competent safety and health personnel to serve as subject experts, technical support, and advisors, and to review and coordinate safety processes. They also tie safety perform-ance to advancement and compensation for all line positions.

At such companies, line managers and safety staff work together at corporate and plant levels to plan meaningful safety improvements and employ the necessary resources to implement them. Reports and audits are prepared with sufficient detail to spot and correct negative trends. Managers, supervisors, and employees are held accountable for quality safety performance. In short, safety is a condition of employment for management as well as employees.

This leads to three conclusions and premises:

1. Senior managers should expect, visibly promote, and support a high level of safety perform-ance on the job. They should implement incident prevention policies, procedures, processes, and systems, and foster a culture that reinforces a safe work environment free of recognized safety and health hazards.

2. Plant managers and supervisors should be responsible and held accountable for a high stan-dard of safety performance. They should institute safe work practices and see that they are followed, maintain facilities in a safe condition, correct safety and health deficiencies in a timely manner, and train employees to recognize hazards and work safely.

3. Employees should perform their tasks safely so as not to endanger themselves, other employ-ees, plant equipment, or processes. They should correct workplace hazards whenever it is within their ability to do so, warn co-workers about hazards they cannot correct, and commu-nicate all pertinent safety and health information promptly to their supervisors (Phelps-Dodge Corporation, 1990).

MOTIVATION

Motivational efforts are designed to modify employee attitudes and behaviors to create a safer workplace (National Safety Council, 1994). To achieve this end, incentives are often used. The two main types of incentives are reactive and proactive.

Reactive incentives tend to reward outcomes, such as low lost time incidence rates. Traditional reactive-type programs employ peer pressure to reduce injuries, but they are generally not effective in maintaining long-term safe work records. They may drive underground reporting of all but the most serious cases, they are not influenced by warning signs such as near-miss incidents, and they do not account for, or correct, flawed or faulty policies, procedures, or systems.

Proactive incentives honor and promote safe work practices. Proactive, process-based motivational systems target upstream activities to influence downstream safety outcomes, much the same as quality or production control equipment or personnel continuously sample and adjust process parameters to manage product quantity, quality, and cost. Upstream safety measures that can be quantified include: 1) interventions in at-risk work practices, 2) reinforcement of observed safe work practices, 3) completion of follow-up actions to prevent recurrence of injury and property damage incidents, 4) reports, investigation, and follow-up of near-miss/near-hit incidents, 5) preparation of and training on Job Safety Analyses (JSAs), 6) employee workplace examinations and subsequent corrections, 7) results of safety audits, and 8) participation in safety meetings or on safety committees.

Conscious efforts should be made to acknowledge safety achievement at every opportunity. Some companies have a Safety Hall of Fame or otherwise recognize those whose adherence to safe work practices, such as lock-out procedures, or seat belt or personal protective equipment use, prevented or lessened injury. Employees can be awarded certificates, plaques, or medals for remarkable, heroic, or life-saving action at or away from the plant. Long numbers of lost-time-free days or man-hours should be celebrated, and significant reductions in incidence or severity rates should be noted, even if some lost time injuries occur, because this encourages further improvement. Every opportunity should be taken to reinforce personal safety values by crediting individuals for their safe work practices or contributions to the safety effort, both publicly and privately.

Psychologists have concluded that the most influential motivators are those with outcomes that are soon, certain, and positive (Geller, 1996). Less effective motivators are those that are delayed, unsure, or negative. Discipline, although a negative factor, is a legitimate motivator, but it must be administered fairly and consistently. Disciplining for incurring an injury is not wise, unless all at-risk behaviors, even those that do not result in injury, are similarly punished. Also, discipline should account for probable severity or degree of risk, and probability of occurrence. Potentially critical or catastrophic issues should be treated differently than less serious ones, and those that are more highly probable warrant stronger action than those less likely to occur.

OWNERSHIP AND EMPOWERMENT

Every opportunity should be taken to involve as many employees as possible in the safety process, and to devolve authority to frontline employees. Widespread participation will pay huge dividends by encouraging personal initiative and reinforcing a sense of individual ownership of the safety process. The more employees think of the safety process as “ours” and not the “the company’s,” the more they will feel empowered to act positively on their own behalf and to improve the system. All employees should be encouraged to serve on safety policy, practice, and inspection committees. They should help investigate incidents, lead safety meetings, make presentations, attend safety seminars and conferences, and write JSAs or safety work orders. This strengthens the system from the bottom up, and creates a wide base on which to build a strong safety culture and a lasting tradition of safety.

COMMUNICATIONS

Interpersonal communication about safety, or any subject, begins with effective listening: employ-ing all of one’s senses to understand the essence and intent of what another is trying to convey. Understanding and employing listening skills and techniques will improve workplace communica-tion, and minimize and help resolve conflict. World-class companies know that in order to opti-mize any workplace function, effective two-way communication is essential. Managers, safety representatives, and employees all benefit from a thorough practice of active and reflective listen-ing, and should know how to enhance communication by questioning, clarifying, summarizing, and providing feedback.

Once good communication principles are understood and established, follow through becomes paramount. Acting on another’s communication displays caring and builds trust. We know from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that safety and security are basic level issues, so if safety problems are considered serious enough to be voiced by an individual or a group, other workplace functions may suffer until resolution is achieved. Therefore,response to real or perceived safety or health discrepancies is very important, and should include feedback.

One should be aware that not all communication is verbal. Body language and facial expressions have an effect when communicating.

Consider also the principle of “silence equals consent” (E. I. du Pont & Nemours Co., 1976). That is, unsafe conditions and at-risk work practices, if observed and not addressed, may send a message that unsafe conditions or at-risk practices are acceptable. The same message may be relayed if at-risk behavior is unseen due to poor observation skills.

There are many ways communications can be achieved in a cement operation, and it is advanta-geous to develop multiple avenues. Published reports on safety statistics offer management and employees a real-time, accurate snapshot of status and progress. They serve as incentives in them-selves and are especially effective when presented in graphic form, or compared to goals, historical data or industry benchmarks. Details on specific plant, company, or industry incidents; root causes; and actions to prevent recurrence give others in the department, plant, or company the opportunity to learn and act before experiencing the same trouble.

Systems should be devised to move relevant information into the workplace, make it readily avail-able, and reinforce other safety and operational processes. For instance, Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDSs) scanned into a computer system can be available at the touch of a button. This enhances compliance, streamlines the process, and makes the information available when needed. It involves employees and makes them more knowledgeable of and comfortable with hazardous material terminology, and results in a better-trained, technologically savvy, self-sufficient workforce.

Other opportunities for communications include bulletin boards, signs, posters, memos, and newsletters. Copies of correspondence and training materials from regulatory agencies should be circulated or posted. Of even more value are opportunities that emphasize two-way communica-tion. Examples of these are departmental safety meetings, especially when hourly personnel participate in leadership functions.

Several companies have developed survey instruments to measure employees’ perception of safety and are one measure of the plant’s safety culture. When trended over time, the results indicate to management its ongoing success in making safety a core value of the workforce, and in responding to needs and concerns. Care should be taken when designing such instruments to query about each of the key elements of the safety process and sample each area uniformly, i.e., phrase questions to gain insight into what respondents think about leadership and commitment, employee involve-ment and ownership, training, communication, motivation, and attitude (Bradford, 2000). Questionnaires range from 1 dozen to over 100 items in length, with professionally designed forms tending to number 70 items or more. Feedback and follow up are critical if such a program is undertaken.

INFORMATION AND MEASUREMENT SYSTEMS

Complete and accurate records of incidents and investigations, inspections, audits, and industrial hygiene surveys are crucial to identifying and correcting workplace hazards. Meaningful record-keeping permits management to review progress toward safety and health goals and objectives. It also measures improvement and reveals trends in safety process performance. Standardized forms, records, and computerized software programs can simplify the collection, distribution, and analy-sis process (National Safety Council, 1994; Phelps-Dodge Corporation, 1990). A variety of programs are commercially available.

Measuring the effectiveness of a safety process requires comparing performance to standards. What the standards are, how high the marks are set, what encouragement or resources are provided to help meet or exceed the goals, and what tolerance is given to falling short or not improving all influence future achievement.

Traditional standards by which cement companies and facilities measure their effectiveness include: 1) the type, severity, and rate of recurrence of incidents of injury, illness, and loss, 2) compliance with government safety and health regulations, 3) adherence to corporate management and insur-ance company expectations, recommendations, and requirements, 4) comparison to local plant, intra-company, and industry performance indicators and trends, and 5) the extent to which proven and successful methods of task performance are known and employed in the workplace.

Outcomes are valid measures, but if used alone, they constitute a downstream, reactive process. Standards that concentrate on failure measurement (incidents, injury and illness frequency and severity, citations, etc.) will not foster safety success, because people will not know toward what they are working. Persons working to achieve something are much more likely to do well than those working to avoid failure (Geller, 1996). Upstream, proactive measures, such as: 1) risk and hazard analyses completed, 2) determination and application of industry best practices, 3) creation of written safe work practices, and 4) percentage of safe vs. at-risk work procedures performed, etc., are measures of a continually improving process.

Operations that see compliance with government regulations as their sole safety standard can be compared to those that accept minimum quality standards. Just as it is unusual in this day and age to market cement that meets only the minimum strength or fineness requirements or has a high standard deviation, it is equally shortsighted to regard regulations alone as the only safety standard.

On the other hand, those that see government standards as a floor level to be exceeded or a spring-board from which to advance have a much better chance of achieving outstanding safety perform-ance. Benchmarking, adopting, and improving on best practices used by successful plants within one’s own organization, and the cement industry as a whole, then looking outside to find world-class practices in related industries will bear much fruit for those who are determined and disciplined.

Audits

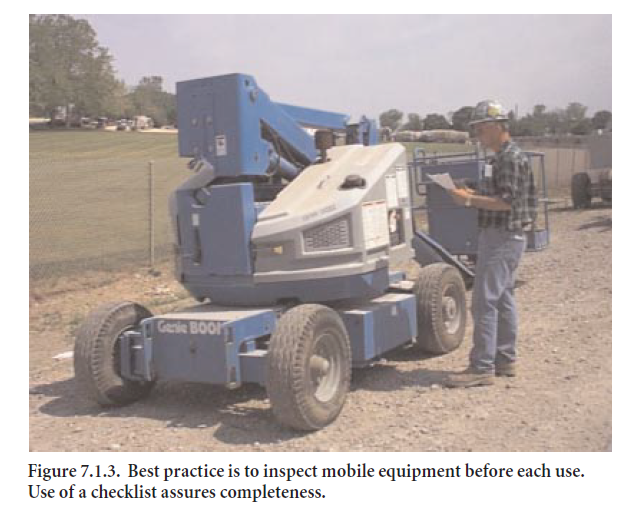

Systematic reviews of plant safety and health processes, and periodic inspection of physical facilities should be performed to assure that conditions, practices, and procedures meet or exceed plant, corporate, and industry standards, and governmental standards and regulations. Individual process components should be examined, and rating systems incorporated to track trends and improvement. Teams of facility personnel who possess good observation skills and are familiar with applicable stan-dards should perform such internal audits. These teams may include technical safety personnel. Departmental leaders or safety representatives may be invited to accompany the team when specific areas are audited. External audits should be conducted by similarly competent persons from the corporate office, another plant, or by safety and health consultants. Audit records should be kept, trends monitored, reports prepared and corrections of deficiencies made in a timely manner.

Audits should assess not only the physical condition of the facility, but also the effectiveness of the management control system as it pertains to safety and health. Audits should identify, measure, and evaluate programs and processes, and compare them to certain standards and accountabilities. Audits should examine: 1) organizational safety policy and procedures, 2) management involve-ment and commitment, 3) effectiveness of hazard identification and control, 4) training, 5) communication, 6) facility housekeeping, illumination, ventilation, and storage, 7) fire prevention and protection, 8) mechanical, electrical, and personal safeguards, 9) incident reporting, investiga-tion, and follow up, and 10) employee involvement and safety competency (National Occupational Safety Association, c. 1995).

Workers’ Compensation Claims and Loss Management

Losses are incurred with every incident that results in injury, illness, property damage or process interruption. These costs are also measures of the effectiveness of a safety and health process, and may be categorized as insured or uninsured. Workers’ compensation, fire, property, and general liability losses are considered insured costs. Uninsured costs include deductibles, lost wages or production, non-productive time of injured employees, overtime for replacement workers, time to report, investigate, keep records, and manage claims paperwork, and repair or replacement of damaged equipment.

Facilities should establish systems to track claims and costs, manage medical provision, and deal with the legal responsibilities that arise out of the process. Insurance carriers, attorneys specializ-ing in workers compensation legislation, and computerized recordkeeping may be of help in managing this process.

Proactive measures that ensure employees receive proper medical treatment and are fully rehabili-tated should begin immediately after any injury. Physicians, the employee, and the company should understand the diagnosis, treatment plan, regular task duties, availability of modified duty, if required, and the projected return to work schedule. Early return to the work environment is advisable to lessen the impact on an injured employee’s earning potential and minimize work disruptions. If an injured worker cannot immediately return to his/her regular job, he/she could still perform valuable services or complete tasks or training while on modified duty that might not otherwise be completed, or done in a timely manner. Therefore, modified work duties should be considered and provided whenever possible in accordance with the work restrictions specified by the physician. Care should be exercised to not jeopardize one’s healing or cause further injury.

TRAINING AND EDUCATION

Training is an essential element in any well-run operation. All employees – hourly and salaried—need a working knowledge of practical communications. They also need an understanding of the overall cement manufacturing process and their part in it.

New employees need an orientation to their work environment and a solid foundation in safety basics. Training topics should include: 1) hazard recognition, avoidance, and report-ing, 2) fire safety, 3) use of personal protec-tive equipment, 4) hand and power tool safety, 5) manual and powered material handling, 6) equipment and guarding, 7) electrical safety, 8) chemical safety, and 9) health and industrial hygiene issues. Workers should have knowledge of safety issues specific to their task assignments and be able to demonstrate safe work procedures. They should understand company, plant, and regulatory policies and standards.

Experienced employees need regular safety refresher training, timely instruction on how changed equipment or processes impact their work environment, and periodic reviews to assure their work procedures correspond to accepted best practices.

Supervisors and managers need to know how to apply leadership skills to safety issues. This includes: 1) understanding and establishing their role in an effective safety organization, 2) setting a safe example and building safety commitment, 3) motivating employees to improve safety aware-ness and performance, 4) maintaining safety standards, 5) monitoring safety status and progress, and 6) managing change.

SAFETY PROCESSES: BUILDING CONSTRUCTION ANALOGY

Keeping in mind that the end use of cement is for construction, consider a building analogy that represents the safety process as an integrated whole.

Structures are designed and built with an end in mind, have a form and function, and make an architectural statement about their use, owner, or inhabitant. They are engineered to account for certain site and use issues such as subsoil conditions, potential seismic activity, weather, and other local environmental realities, and they are finished and furnished to facilitate effective business.

The setting and environment in which the building is sited represents the industry (cement). Architects and engineers (safety and health professionals) assess the scope of work (equipment and processes) and end use (hazard analysis),design the building’s size, and arrange it to meet certain occupancy needs (hazard evaluation and controls).They draw the blueprints for construction (workplace design standards),applying accepted or minimum engineering and construction stan-dards (safety regulations and life safety codes) by which the building is designed and periodically checked to confirm compliance and safe occupancy. The soil on which the building is constructed (organizational safety principles and values), and the foundation (key principles of successful safety management) undergird the whole and determine its stability. Columns and beams (fundamental safety and health elements) frame the structure and give shape to the whole.

Attached to the skeletal structure are floors, walls, and interior and exterior finish (safe work procedures and detailed basic programs) that finish the structure and make it usable. Supervisors direct operations (line manage-ment safety responsibility) and people in the building work according to certain standards (safe vs. at-risk practices), thereby defining the culture (assessments, audits, statistics, and other measures) (Bradford and Kirk, 2000).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This chapter was prepared by the author for review and consideration to raise awareness of health and safety issues in the cement industry. Its contents reflect solely the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Portland Cement Association or its members. The contents are not intended to provide authoritative language applicable to all safety aspects about cement manufacturing and in no way replace the obligation to follow applicable laws and regulations.

REFERENCES

Agricola, Georgius, De Re Metallica, 1556, translated from the original Latin by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover, published in “The Mining Magazine,” London, England, 1912, reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1950.

American Society of Safety Engineers, CSP Refresher Guide, Des Plaines, Illinois, 1991.

BHP Minerals Inc., Benchmarking Safety 94-95, San Francisco, 1995.

Bradford,David M., Sustaining Injury-Free Performance, Behavior Safety Systems, Hockessin, Delaware, 2000.

Bradford, David M., and Kirk, L. Harvey, respectively of Behavior Safety Systems, Hockessin, DE; and CSP, Walkersville, Maryland, 2000.

Eckenfelder, Donald J., Values-Driven Safety: Reengineering Loss Prevention, Government Institutes, Inc., Rockville, Maryland, 1996.

E. I. du Pont & Nemours Company, Inc., STOP for Supervisors, Wilmington, Delaware, 1976.

Geller, E. Scott, Ph.D., The Psychology of Safety, Chilton Book Company, Radnor, Pennsylvania, 1996.

Hethmon, Thomas, Phelps-Dodge Corporation, Phoenix, 2000.

Joseph Austin Holmes, MESA Magazine, March/April 1976, Washington, DC, reprinted by the Holmes Safety Association Bulletin, February 1994, Mine Safety and Health Administration, US Department of Labor, US Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Markiewicz, Dan, “Are You Ready to Talk About Risks?” Industrial Safety & Hygiene News, Business News Reporting Company, Troy, Michigan, July 2000.

Minerals Council of Australia, Safety & Health Performance Report of the Australian Minerals Industry, 2000-2001, Braddon ACT, Australia, 2002.

Morrisey, George L., Morrisey on Planning: A Guide to Strategic Thinking – Building Your Planning Foundation, Jossey-Bass, Inc., San Francisco, 1996.

National Occupational Safety Association, MBO 5 Star Safety & Health Management System, Arcadia, Pretoria, South Africa, 1995.

National Safety Council, 14 Elements of A Successful Safety and Health Program, Itasca, Illinois, 1994.

Nelson, Emmitt J., “Safety Commitment Redefined,” Professional Safety magazine, American Society of Safety Engineers, Des Plaines, Illinois, 1998.

Phelps-Dodge Corporation, Safety and Health Guidelines, Phoenix, 1990.

Plog, Barbara A.; Niland, Jill; and Quinlan, Patricia J., Fundamentals of Industrial Hygiene, Fourth Edition, National Safety Council, Itasca, Illinois, 1996.

Tregoe, Benjamin B., and Zimmerman, John W., Top Management Strategy: What It Is and How to Make It Work. Simon & Schuster, New York, 1980.

Wilson, Larry, “Behavior-Based Safety: Better Methods, Better Results,” Occupational Health & Safety magazine, Stevens Publishing Corp., Dallas, June 2000.