Contents

To download the below and all other Useful Books and calculations Excel sheets please click here

To download the below and all other Useful Books and calculations Excel sheets please click here

Kiln Systems and Theory – History

Vertical furnaces and simple forms of shaft kilns were used for burning lime well over 2,000 years ago. History tells us that the Romans used a vertical furnace in which to bum a pozzolanic lime. Near Riverside, California are the remains of underground furnaces (Fig. 1.1) in which the early Mexican settlers burned limestone to make lime during the first part of the 19th century. In later times so-called bottle and shaft kilns were em ployed. Vertical kilns of the type shown in Fig. 1.2 were constructed in Southern California about the tum of the century.

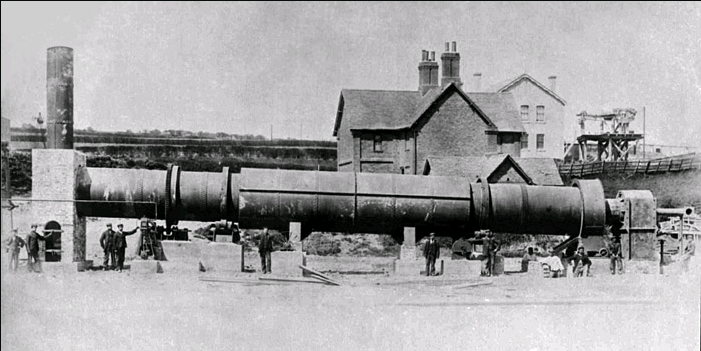

Early development of the rotary kiln probably started about 1877 in England, but Frederick Ransome is usually credited with the frrst successful rotary kiln, which he patented in England in 1885. Although the first Ransome kilns were a major breakthrough in the cement industry at that time, many years passed before a successfully operating rotary kiln was put into production. It was mainly the pioneer work of American engineers a few years after Ransome’s discovery that brought the concept of the rotary kiln out of its infancy. The first economical rotary kiln in America, developed by Hurry and Seaman of the Atlas Cement Company, went into production in 1895.

Shaft kilns with continuous feed are now used mainly and only for the burning of lime and minerals other than cement Rotary kilns have re placed these shaft kilns entirely in the cement industry. Although years ago, shaft kilns showed lower thermal and power requirements than rotary kilns, the advent of the preheater and precalciner kilns with their increased output and fuel efficiency has apparently made the shaft kiln obsolete for the burning of cement clinker.

Fig. 1.1 Remains of undcrp,round furnaces that were used by early California Sctllers for burning limestone to make lime. (Riverside Division, Ameriam Cement Corp.)

The first Ransome kilns were 45 em (!8 in.) in diameter and 4.5 m (15 ft) in length. Later, about 1900, the rotary kiln grew to !.8 m (6ft) in diameter by IS m (60ft) long which in todays terms would have to be classified as miniatures. Kiln sizes really started to explode in the 1960’s when they reached dimensions up to 6.5 m (21 ft) diameter and up to 238 m (780 ft) length. With these enormous sizes and corresponding high output rates a considerable amount of new structural and control problems started to evolve. Refractory life in tlw kiln became uneconomically low, coolers couldn’t handle that high output especially not during upset conditions, and mechanical equipment failures became weekly occurrences in many plants.

The energy crisis represented a blessing in disguise in matters of kiln design. Suddenly, fuel conservation became the number one priority item in most cement plants which led directly to increased construction of preheater kilns all over the North American continent. Although these preheater kilns satisfied the need for lower fuel consumption, they didn’t meet the requirements for using low-grade fuel and ever-increasing demands for higher production rates.

Fig. 1.2 Vertical shaft kilns were commonly in use in the latter part of the 19lh century. (Riverside Division, American Cement Corp.)

In an attempt to gain these higher outputs, the Japanese cement indus try increased preheater kiln sizes to a point where they were back to square one, namely, these kilns again became too large; frequent mechanical problems and short brick-life became the norm just as in the times of the dry and wet monster kilqs. The major breakthrough came in Europe where precalcination was successfully attempted in the late 1960’s using a very low bituminous shale as a component of the kiln feed in a conventional preheater kiln. Adding combustible materials to the kiln feed, at that time, was nothing revolutionary, for the author himself, in 1957, had burned a wet kiln in Canada that contained oil shale in the slurry. The European experience, however, was the first time such an addition was successfully tried in a preheater kiln and thus paved the way for today’ s precalciner kiln. Precalciner kilns are the latest advance in cement manufacturing technology. They combine low thermal requirements, are able to use low grade fossil fuels or other combustible materials, and show output rates that were considered unattainable only a few years back.

TO BE CONTINUED….